The social determinants of health are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes, that is, the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age.1 They include income, education housing, and access to healthy food and health services. Research shows that social determinants can be more important than healthcare or lifestyle choices in influencing health.

Racial Bias

For example, a recently published study showed that living in a racially segregated neighborhood puts Black children in the U.S. at a higher risk of having elevated blood lead levels and the environmental and social burdens that accompany that.2 Another recent study of more than 50,000 U.S. adults suggests that social determinants of health are a major contributing factor to higher mortality rates from cardiovascular disease in Black individuals compared to Whites.3

Substandard Housing

People who suffer from chronic homelessness have a shorter life expectancy and starkly higher rates of many chronic illnesses, including HIV, diabetes, hypertension, depression, hepatitis C and substance use disorders.4 While poor health is sometimes a cause of homelessness, the state of being homeless itself can create new health problems or exacerbate old ones.

Food Insecurity

Unhealthy diets increase the risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, certain cancers and the likelihood of obesity.5 Food insecurity can also lead to people avoiding eating. Going hungry, even just a few times, is linked to decreased immunity and poorer mental and physical health, and can cause malnutrition, heart disease and fatigue.

Pandemic Exposes Inequities

Social determinants affect the health of people around the world, and since the COVID-19 pandemic, inequities have widened. During the pandemic, 600,000 excess deaths in the World Health Organization European Region were attributable to low investment in human development and healthcare.6 Disabilities have also increased, particularly among the most disadvantaged, with people on a low income twice as likely to have a limiting illness compared with those on a high income. This gap has widened by 5% since the pandemic.

Health services are increasingly under strain and unmet needs are increasing, particularly for the most disadvantaged people. Those on a low income are 70% more likely to have unmet needs for healthcare compared with those on a high income. Following the pandemic, an additional14 people per 1,000 population had an unmet need for healthcare compared with before the pandemic.

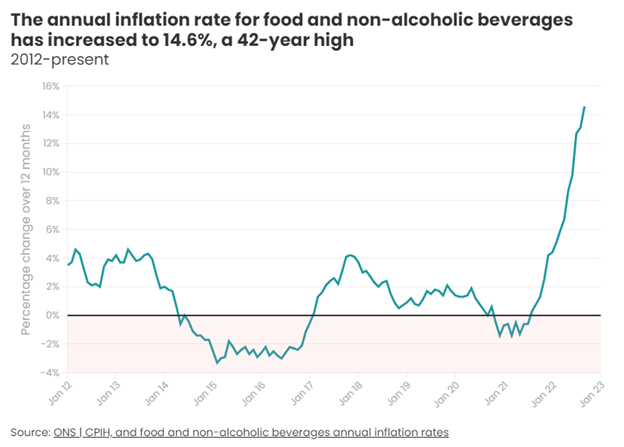

In 2022 food prices increased by 40–70% in central Asia, the Caucasus, central Europe and southern Europe. Food insecurity was already rising in these parts of the WHO European Region in 2021. The United Nations Children’s Fund has estimated that this crisis will lead to 10 million more people in poverty and 4,500 more infant deaths in central Europe, the Caucasus, the Russian Federation and central Asia.

Time for Action

Some healthcare providers have taken it upon themselves to directly address the social determinants of health of their communities.

In Virginia, for example, Bon Secours Richmond has provided $8 million in affordable housing grants over the last 10 years.7 The University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System in Chicago has contributed $1.5 million to a program through which patients who are chronically homeless and frequent Emergency Department users can get temporary housing until more permanent accommodations can be found. And Boston Medical Center, in conjunction with the local housing authority, established the “Elders Living at Home” program in 1986 to assist frail elderly people displaced from their apartments.

Food insecurity is another issue that some health systems are addressing. The American Hospital Association has advised its members to screen for food insecurity; educate patients about available federal nutrition programs; connect patients and families with dietitians and nutritionists for counseling services; provide free food or healthy snacks at clinics or on-site food pantries; or develop on-site food pharmacies, food pantries and community gardens.8

Future directions

As healthcare professionals learn more about social determinants of health, they face new challenges. One such challenge is health literacy, that is, an individual’s ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions.9 Perhaps not surprisingly, personal health literacy skills are unevenly distributed across populations, with lower skills disproportionately affecting American Indian and Alaska Native, Black and Hispanic people.

Another challenge is a growing recognition of potential biases in artificial intelligence and machine learning, technologies expected to play a big role in clinical decision-making.10

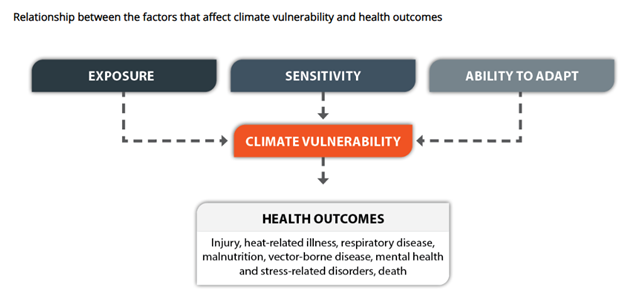

Meanwhile, climate change is expected to exacerbate health inequity. For example, people with limited income are more likely to live in subsidized housing, which is more likely to be in areas that are prone to flooding.11 Such housing might come with mold problems, inadequate insulation or inadequate air conditioning.

Some physicians and researchers believe that education on the health effects of socioeconomic factors should begin in medical school.

“Last month I gave a lecture to first-year medical students on a topic that is foundational to their future practice of medicine,” wrote emergency physician and researcher Dr. Kelly Doran recently, referring to a lecture he gave as part of the first-year curriculum at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “No, it was not on the Krebs cycle. It was a lecture on homelessness, something that impacts nearly 600,000 people on any given night in the U.S. and that has profound negative health effects, up to and including premature mortality.” It was the first time such a lecture had been required for first-year medical students at the school.

“While medical students and physicians generally cannot immediately solve a patient's homelessness, we can and should ensure that the medical care we provide is appropriate, in addition to offering social work assistance or referrals to local community resources,” wrote Dr. Doran.12

References

- Social determinants of health, World Health Organization

- New research establishes enduring connection between racial segregation, childhood blood lead levels, ScienceDaily

- Social, Behavioral, and Metabolic Risk Factors and Racial Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in U.S. Adults, Annals of Internal Medicine

- To improve health, hospitals partner to provide housing, AAMC News

- Why preventing food insecurity will support the NHS and save lives, NHS Confederation

- Transforming the health and social equity landscape, World Health Organization European Region

- To improve health, hospitals partner to provide housing, AAMC News

- Hospitals and food insecurity, AHA Trustee Services

- Health Literacy and Systemic Racism – Using Clear Communication to Reduce Health Care Inequities, JAMA Internal Medicine

- Unequal Treatment at 20: Accelerating Progress Toward Health Care Equity, Urban Institute

- Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Climate Adaptation Planning, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Medical School Should Teach Students About Homelessness, MedPage Today

Share Article